A Sweeping, Historic Landmark

It doesn't take much to prod us media types into adjectival overload.

It doesn't take much to prod us media types into adjectival overload.In our kit bag of clichés, every reform must be sweeping, every bill a landmark, every debate historic.

It reminds me of George Bernard Shaw's observation about the failing of the media of his day – it's inability to distinguish between a bicycle accident and the collapse of western civilization.

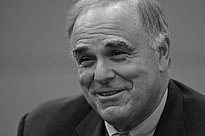

But, I do think we had a genuine, bona fide historic moment this week when Gov. Rendell signed the property-tax reform bill.

It was the culmination of a 50-year debate over how to wean local governments off reliance on property taxes as the principal means of paying for public education.

During that half-century, there was widespread agreement – at least among political and government types – that taxes on property tended to be unfair, cumbersome to administer and unsuited to the needs of modern government. An 18th century relic in the 21st century state.

There was even agreement on what to do about it: shift from reliance on property taxes to some form of income tax or consumption tax.

This was the suggestion of study commissions and tax legislation championed by George Leader, Milton Shapp, Dick Thornburgh and, most famously, Bob Casey Sr.

Casey even got the legislature to agree to a plan to reduce property taxes by increasing local income and sales taxes.

Because it required a Constitutional amendment, it was presented to the voters, who shot it down in 1989 by a 3-1 margin.

The whys and wherefores of that defeat have been picked over for years, but I'll try to summarize.

One. Such plans tend to be complex. In theory, it is a simple transaction – resembling a seesaw – property taxes go down, while other taxes go up to an equal degree.

In reality, because of the nature of the legislative process, what usually emerges is a three-dimensional hexahedral structure resembling Crick and Watson's model for DNA.

Second. People don't like taxes. When they think taxes, they don't want shift, they want cut. They are also suspicious, and rightly so, that when politicians say shift, they really mean increase.

They look at that hexahedral structure, with its interlocking strands, and say: Screw it!

The central tension of government is that people love the services it renders and loath the taxes required to pay for them. Partisan politics feeds on that contradiction.

To quote Sen. Russell Long, the attitude of most folks is: "Don't tax you, don't tax me, tax that fellow behind the tree."

Well, Ed Rendell found someone behind the tree willing to pay the tax.

Donald Trump.

There were legislators, particularly Republican legislators, who abhorred Rendell's idea of introducing casino gambling into the state. But, they loathed raising taxes even more. In effect, they became gambling's enablers.

There were others (I'm in this group) who thought it would be cleaner, simpler and more sensible to raise the sales or income tax to pay for the property tax relief. But they had gotten nowhere for 50 years.

Rendell's gambling idea changed the debate because it had an alluring aspect for legislators in both parties: When it came to taxes, why fight over how to slice the pie, when you can bake a whole new pie? The aroma of $2 billion in slots revenue proved irresistible.

You have to give Ed Rendell credit or, conversely, you have to curse him.

He came into office saying he would do two things:

One. Increase state taxes so we can increase the state's share of paying for public education, thus relieving local government of some of its burden. He did that.

Two. Cut local property taxes by introducing casino gambling into Pennsylvania. He did that, too.

And he seems perfectly happy to stand on that record as he seeks re-election.

Come to think of it, maybe that's another sweeping, historic landmark, too.